Evo 2: Arc’s DNA Foundation Model Explained

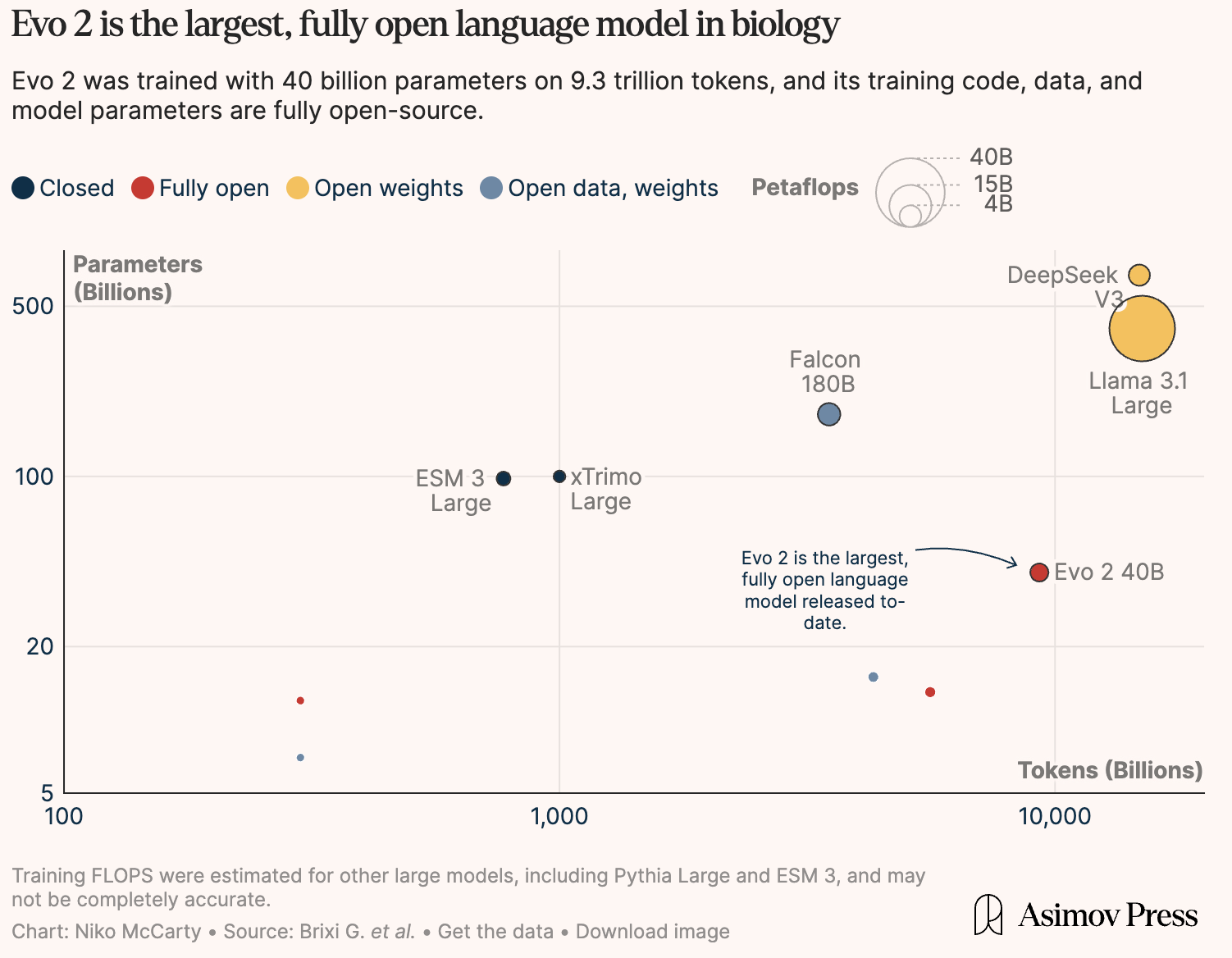

In February, Arc Institute released Evo 2, a DNA foundation model trained on genomes from all domains of life. According to Arc, this represents the largest training effort in computational biology to date, with novel architectural advances to handle genomic sequences.

Over the past few decades, synthetic biologists have dreamed of programming cells as easily as we program computers: creating bacteria that clean up pollution, crops that thrive in extreme environments, or therapies that target disease at the genetic level. Traditionally, this has required painstaking manual design and years of trial and error. Evo 2 represents a potential leap forward: what if we could generate entirely new genomes in silico, rapidly and at scale?

Over the past few days, I got curious about Evo 2, initially because of the application of a non-Transformer architecture and the nuances of modeling on genomic data. Quickly, I found myself diving through Wikipedia and Deep Research reports to understand the biological concepts and the technical details of Evo 2. This post is a distillation of my understanding of Evo 2, which I hope will be useful to anyone interested in learning more about the intersection of LLMs and biology.

By the end of this post, my goal is for you to understand (1) why genomic sequence modeling can't simply rely on off-the-shelf Transformers, (2) how Evo 2 can be useful in today's biological workflows and (3) how Evo 2 and similar genomic foundation models may evolve in the future.

Overview

Unlike modern LLMs, which are optimized for the constraints of natural language, Evo 2 is tailored to genomic sequences. From a low-entropy vocabulary to long-range dependencies between tokens >1M tokens apart, modeling genomic sequences is quite different from natural language.

Evo 2 is a successor to Evo, which was the first large genomic language model released by Arc back in early 2024. Evo showed that large, long-context genomic DNA foundation models could viably generate “realistic” genomic sequences. But, Evo only focused on prokaryotes, and didn’t generalize well to human genomes. To accurately predict animal and human genomic sequences, Evo 2 also trained on eukaryotic genomes and modified the architecture of Evo to work for the larger genomes in eukaryotes.

Evo 2 was trained on over 2,000 H100 GPUs for several months, putting the estimated cost of the run at ~$10M. With Evo 2, you can:

- Generate novel genetic sequences across both eukaryotes and prokaryotes that exhibit high fitness.

- Predict the functional impact of specific genetic variants, such as BRCA1 mutations linked to increased breast cancer risk.

- Improve sequence‐fitness predictions at inference time: giving the model more compute resources during inference leads to better genomic‐fitness estimates, similar to how test‐time scaling boosts reasoning performance in LLMs.

- Handle up to 1 million base pairs of context when generating sequences.

- Leverage mechanistic interpretability to see what Evo 2 “learned” from raw genomic data.

On paper, Evo 2's capabilities are impressive, but I want to know how Evo 2 really works. Sure, by increasing the dataset size, model size or compute, you expect language models to get better. What makes Evo 2 so performant at genomic modeling?

Quick Primer

To make sure that you don’t get overwhelmed by the breadth of biological knowledge to understand Evo 2 and spend several hours asking questions to your favorite reasoning model, I’ve distilled some basic biology concepts relevant for understanding Evo 2 here. These include both the data that Evo 2 is modeled on, and some terms for the tasks that Evo 2 is applied to. If you're already familiar with these concepts, feel free to skip to the Training & Architecture section.

Genome Modeling

Nucleotide Sequences

Evo 2 models DNA sequences. These linear sequences are composed of nucleotides that encode genetic information: adenine (A), guanine (G), cytosine (C), and thymine (T). According to the paper, Evo 2 also pre-trains on RNA sequences, and RNA sequences use Uracil (U) instead of Thymine (T). In DNA, this is abbreviated as “AGCT”, and in “RNA” as “AUCG”. I’ll refer to them as nucleotide or genomic sequences throughout the rest of the post.

DNA → RNA → Protein

Evo 2 explicitly models DNA sequences and RNA sequences because it’s pre-trained on them. But how does it model protein sequences? DNA and RNA contain the instructions for protein synthesis, so Evo 2 can learn statistical and structural features of DNA/RNA that implicitly encode proteins. Evo 2 learns which RNA transcripts are likely to be stable, expressed and translated into functional proteins. When I cover mechanistic interpretability with Evo 2, I’ll show specifically how it has internalized these features. This is known as the “central dogma”, with the caveat that RNA does more than just implicitly encode proteins (obligatory XKCD #3056).

Variant-Effect Prediction

Computational bridge from raw mutation to clinical decision, based on a genetic mutation you can determine if a specific condition is more likely.

SNVs

Single nucleotide variant - a change in a single base in the genome sequence. Most are benign and some are harmful.

Variant Pathogenicity

How likely a genetic variant (usually an SNV) is to cause disease. Falls into 3 categories: pathogenic (causes disease), uncertain significance and benign.

BioML

To contextualize Evo 2, it’s also important to understand the lineage of models that it follows. There are two main model lineages that are relevant to Evo 2, large protein language models, trained on protein sequences, and large genomics models, trained on genomic DNA sequences.

AlphaFold, one of the first large protein language models (PLMs) came out in 2020 and predicted protein structures. It clearly demonstrated how ML algorithms can “learn” biological structures better than humans for laboratory relevant tasks. Then in 2021, ESMFold demonstrated how the transformer architecture could be applied to protein sequences to predict structural features purely from the embeddings of large-scale PLMs.

Around 2021, most genomics modeling was highly task-specific. Models such as Enformer and GenSLM were used for epigenomic signals and microbial genome generation, but didn’t generalize well beyond their training set. In 2024, Evo marked a similar transition to ESMFold, but for genomics data. Evo was the first model to show that a long-context genomic sequence model trained on generic prokaryotic data could yield sequences with high prokaryotic sequence fitness without any task-specific fine-tuning. Evo 2 naturally followed Evo, but with architectural changes to perform well for eukaryotic data.

Training & Architecture

With this background on the biology and model lineages behind Evo 2, let's dive into what's new and unique about the Evo 2 architecture.

Evo 2 uses a “multi-hybrid” architecture, a Transformer-like architecture that performs better for the longer context required for genomic modeling using convolutional operators. In this section, I'll go over the Evo 2 architecture, StripedHyena 2, and Evo 2's training recipe.

Architecture Motivations

The motivations for Evo 2’s architecture are quite different than those for traditional LLMs.

- The context length required for effective genomic modeling is on the order of millions of base pairs due to long-range dependencies between nucleotides. In large nucleotide sequences, “far-apart” bases can still interact with each other. Nucleotide strands fold in 3-D and folding will pack distant nucleotides side by side. In fact, SNVs can cause conditions such as thumb duplication.

- The vocabulary size for Evo 2 is O(10), with most tokens concentrated in the nucleotides for DNA, AGCT, and RNA, AGCU. This is drastically smaller than the vocabulary size in modern LLMs, which are typically between 10K to 100K tokens.

- Single-nucleotide resolution is critical. To make clinically relevant predictions for SNV’s (among other targets), you need to know exactly which nucleotide changes. Increasing the size of the vocabulary to reduce the context length is a patchwork solution and is untenable for this reason.

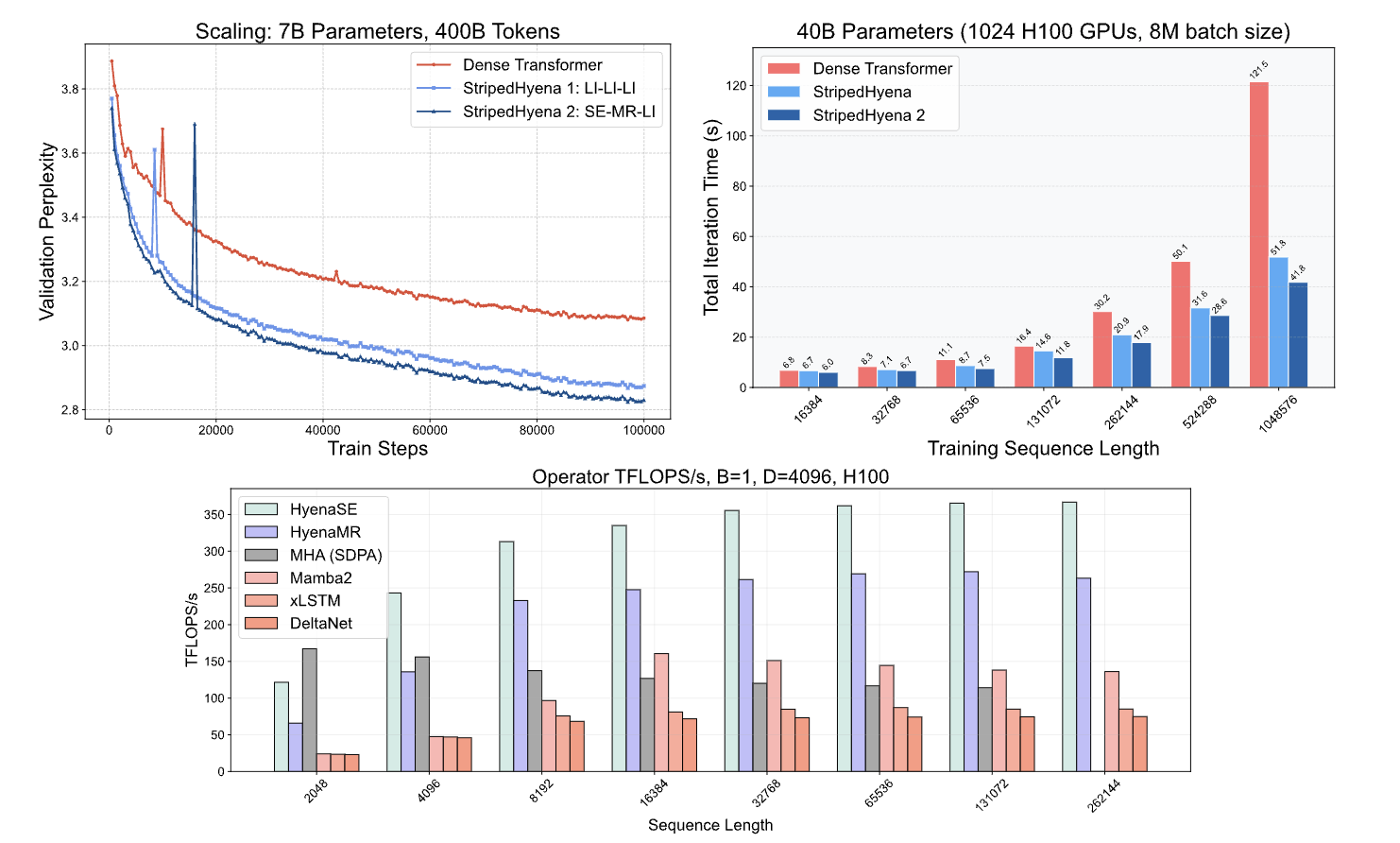

Traditional transformers that are used for language modeling are not able to effectively handle 1M tokens of context with global long-range dependencies. Most LLMs (e.g. GPT-4o, Claude4) max out at a 200K context window due to the quadratic compute requirement for attention.

Methods of achieving longer-context with transformers such as local + periodic global attention still don’t reduce this compute budget requirement. So, out-of-the-box transformers will be quite expensive for modeling genomic sequences at the scale of millions of tokens. Can we use convolutional operators to do better, while retaining the benefits of transformers?

StripedHyena 2 Architecture

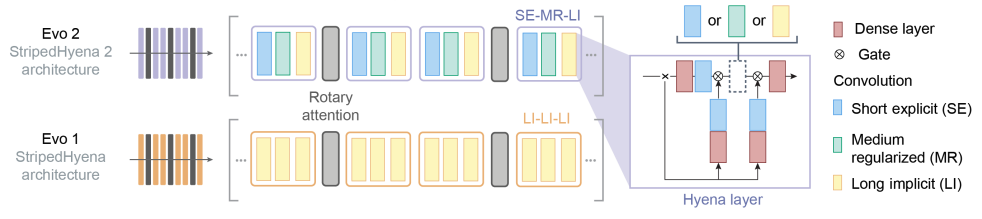

Before explaining Evo 2’s architecture, Striped Hyena 2 (SH2), I’ll explain Striped Hyena 1 (SH1), the architecture for Evo. Striped Hyena is a part of a family of architectures that use convolutional operators to model long-range dependencies in combination with attention.

Speficially, SH1 combines the Hyena state-space convolution with self-attention layers. SH1 is similar to Mamba, except that SH1 fuses the convolutional operators and attention layers to push more computational efficiency and tighter coupling of local & global features. Mamba’s simple sequential convolution → attention blocks can fit into existing Transformer pipelines, whereas SH1 requires custom fusion logic. Because SH1 is applied to genomic data, where the context length is much longer than in language modeling, this tradeoff makes more sense. Fusing together the attention and convolution blocks amortizes the overhead to reduce inference and training compute, which yields 2x speedup over dense transformers.

Mamba and SH1 are known as “hybrid” architectures because they combine two key components: attention and state-space convolutions.

Evo 2’s architecture, called SH2, builds on this idea by using a mix of attention layers and three types of convolutional operators—short, medium, and long. Each operator is specialized: short convolutions capture local (nearby) dependencies, medium convolutions handle patterns over hundreds of tokens, and long convolutions capture relationships across very long stretches of the sequence. This combination is why SH2 is referred to as a “multi-hybrid” architecture.

A major advantage of SH2 over SH1 is its use of multiple convolutional layers, rather than just Hyena-LI, which increases training and inference speed. Specifically:

- Hyena-SE (Short Explicit filters): Focuses on recalling information from nearby tokens (local context).

- Hyena-MR (Medium Regularized filters): Handles dependencies over several hundred tokens, maintaining efficiency and performance.

- Hyena-LI (Long Implicit filters): Captures long-range dependencies across the sequence.

The ML paper for Evo 2 draws a nice parallel between the new convolutional operators and the classic attention operator.

Hyena-MR is to Hyena-LI what sliding window attention is to the classic attention operator.

By leveraging more efficient convolutional operators for short, local recall, SH2 gets a 2x-3x speedup in training over SH1. SH2 only pays for long-range context occasionally, rather than in each layer.

Below, you can see the scaling results for a dense transformer against SH1 and SH2. At longer contexts, you can clearly see that the Hyena-SE and Hyena-MR convolutional kernels out-perform MHA (multi-head attention) as you’re no longer paying the quadratic overhead of attention. The use of Hyena-SE and Hyena-MR kernels increases training and inference throughput.

More details on how the convolutional kernels are implemented + further results can be found in the Evo 2 paper and the sister ML paper.

With this background on the architecture, let's dive into the training data and training recipe for Evo 2.

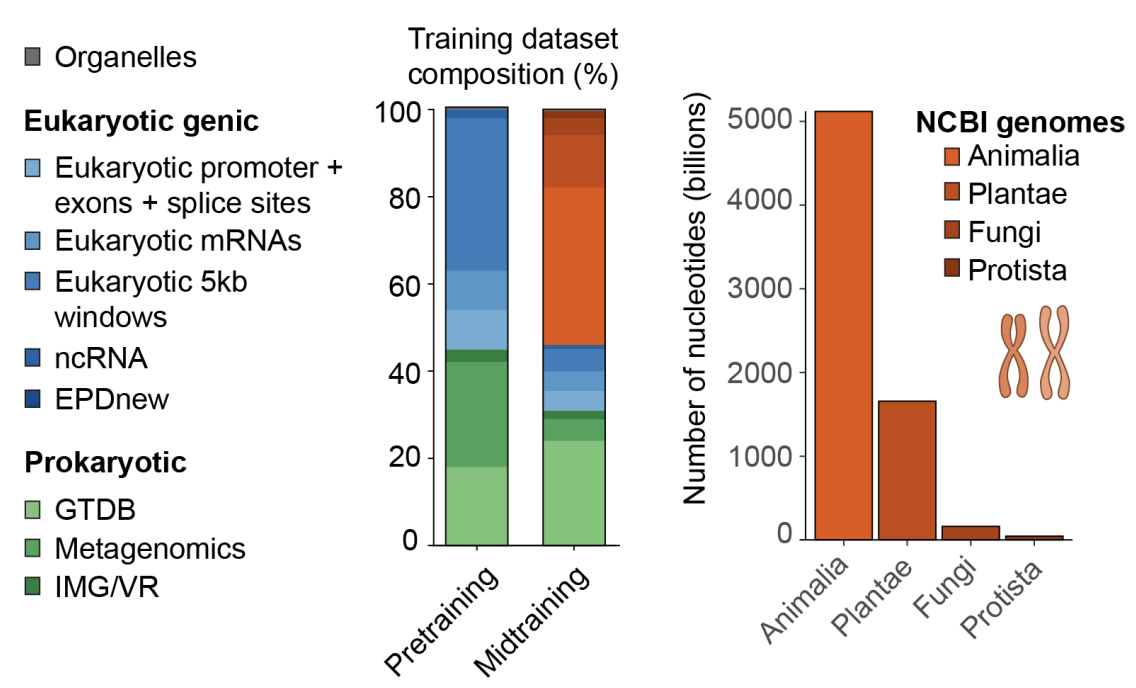

OpenGenome2 Dataset

Evo 2’s training data (called OpenGenome2) comprises over 9T DNA base pairs spanning all domains of life (bacteria, archaea, eukarya).

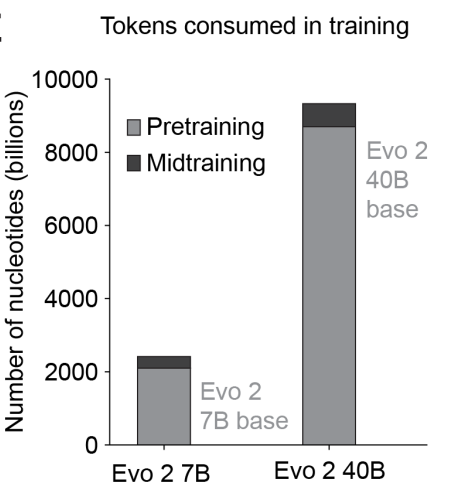

To capture both local functional elements and long‑range genomic dependencies, two training phases were employed: an initial “short‑context” pretraining on 8,192‑bp windows enriched for genic regions, followed by a “midtraining” stage that extended context to 1M base pairs, with sequence composition shifted toward whole‑genome samples. By combining these two training phases, Evo 2 achieves single‑nucleotide resolution and the diversity needed to generalize across everything from mitochondrial micro‑genomes to complex eukaryotic chromosomes.

As seen in the charts below, the vast majority of FLOPS are applied in pre-training. During pre-training, the model gathers knowledge about biological structure, and mid-training extends this structure from just eukaryotic genes to genomic sequences from the genome data bank.

Now that you have a basic understanding of the training data and architecture of Evo 2, let's dive into how to use Evo 2 to generate novel genomic sequences.

Generating Genomic Sequences

Evo 2 can generate new DNA sequences by starting from a short input sequence and predicting what nucleotides come next, one base at a time. Evo 2 can be used to generate novel sequences with no guidance (zero-shot novel generation), or to search for a sequence that meets a specified goal (directed search).

Zero-Shot Novel Sequences

The API for requesting a genomic sequence from Evo 2 is quite simple: pass the input and the number of additional tokens and the model will generate the corresponding nucleotides after the initial sequence.

=

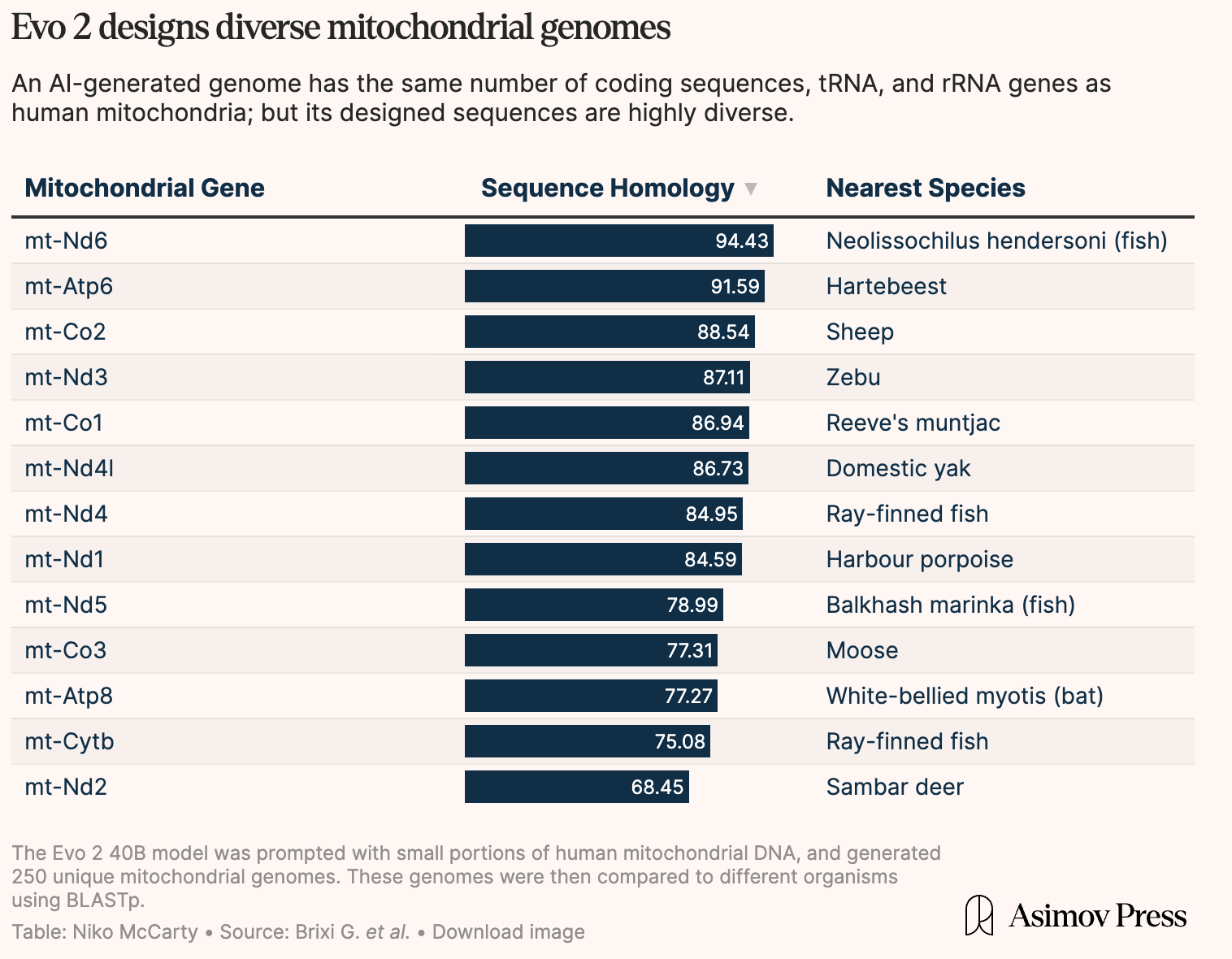

To demonstrate how Evo 2 generates “novel” genomic sequences and generalizes well, the Evo 2 team generated a diverse set of “viable” eukaryotic genomes starting from a human mitochondrial sequence.

Using BLAST analysis, they verified that the generated mitochondrial DNA sequences were similar to naturally occurring organisms. Then, with AlphaFold 3, they validated that the generated structures matched expected mitochondrial protein complex folds. In simpler terms, scientists check that both the “sequence” and the encoded proteins from the sequence are “viable”.

Below is a sample of how the Evo 2 model was used to generate a set of genomes from a small human mitochondrial DNA seed. The generated genomes ranged from being most similar to a sheep or a fish, all from the same human mitochondrial seed.

As you can see, the generated sequences are quite diverse, and have some measure of biological viability. Designing "natural-looking" genomic sequences is cool, but not what you'd do if you wanted to create a new organism. How can you get a sequence that meets a specific goal - say a sequence that's more likely to bind to a protein target?

Scaling Inference-Time Compute

Unlike traditional LLMs which can be prompted with additional language context to steer the output of generation, Evo 2 can only process nucleotide sequences as input. Once you’ve generated a genome, there’s no way to guide the model in a specific direction with natural language.

So, how do you do directed search for nucleotide sequences that have specific conditions beyond “natural viability” at inference-time?

For this, we can look to modern ML, where scaling inference-time compute has been widely adopted over the past year. At a high level, techniques for scaling inference-time compute can be broadly categorized into self-refinement and searching against a verifier.

In genomic sequence generation, there are many heuristics (known and unknown) that you may want to optimize a sequence for. This is in contrast to language models, where "more intelligent" answers is generally a 1-dimensional metric to optimize for. To handle this complexity, the Evo 2 team chose to demonstrate searching against a verifier with beam search in their paper, which can be easily adapted to other heuristics.

Beam search is a method for generating sequences where, at each step, you generate N possible candidates from the current sequence. Each candidate is scored using a heuristic function that measures how well it meets the desired criteria. Out of all the candidates, you keep only the top K sequences with the highest scores. This process repeats for each new step, always expanding and selecting the best K options, until the full sequence is generated.

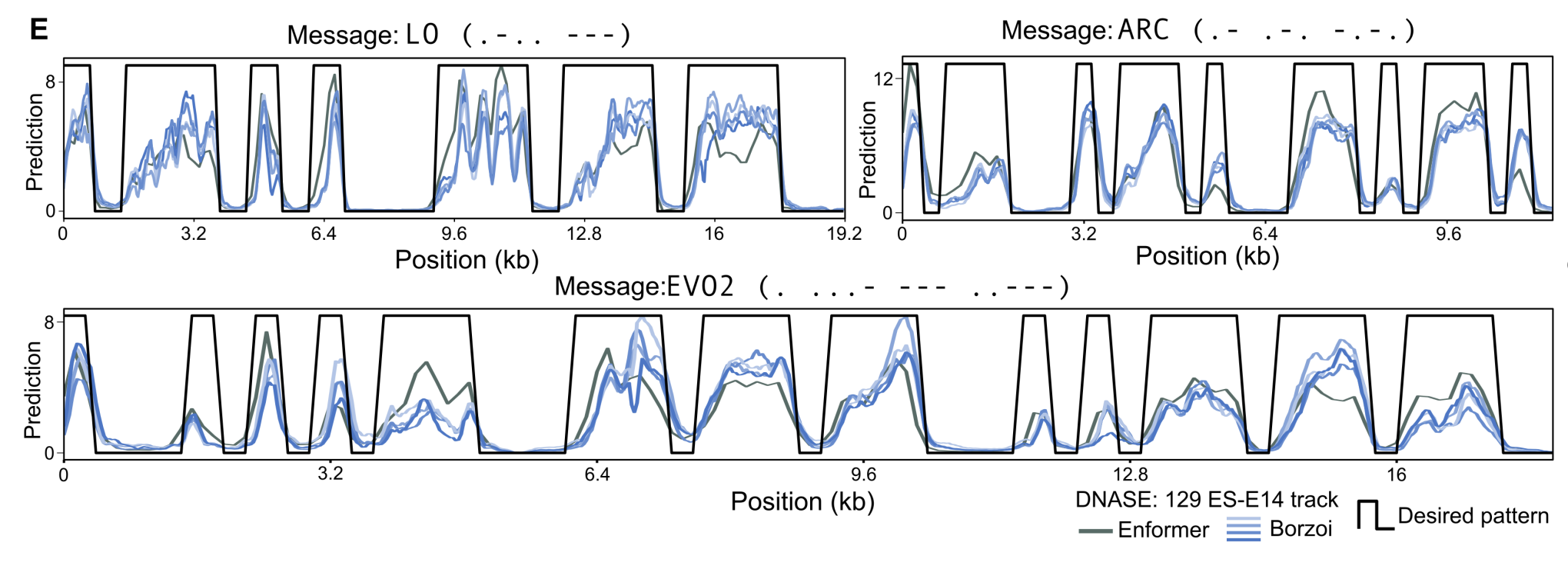

Let’s walk through how the Evo 2 team uses beam search to generate proteins for a specific heuristic: chromatin accessibility patterns. Chromatin accessibility refers to how “open” or “closed” regions of DNA are.

Evo 2 uses Enformer and Borzoi as heuristic functions for evaluating a generated sequence. Both models yield whether a nucleotide will have accessible chromatin given a window of nucleotides around the target. With beam search, Evo 2 guides the generated genomic sequence to encode specific chromatin accessibility patterns in nucleotides with the following protocol:

- Sample N times (fan-out) from Evo 2 given the same prompt.

- Score the N samples with Enformer and Borzoi.

- Select the top K sequences based on their scores and use them as the starting point for the next generation step.

- Repeat until you’ve generated a nucleotide sequence of length L.

With this approach, the Evo 2 team was able to generate genomic sequences that encode chromatin accessibility patterns that match the Morse code encoding of “Evo 2” and “ARC”. You can see these encoded in the chromatin accessibility diagrams below.

By scaling inference-time compute, the Evo 2 team demonstrated how to steer the generation of a sequence to meet a specific heuristic function. Scaling inference-time compute is powerful for guiding sequence generation, but ultimately, the diversity of genomes Evo 2 can produce is bounded by what the model has learned.

Evo 2 + Mechanistic Interpretability

Mechanistic interpretability can help reveal the underlying biological concepts and genomic features that Evo 2 is capable of generating.

The Evo 2 team worked closely with Goodfire to train sparse auto-encoders (SAEs) to uncover the latent concept representations within Evo 2. SAE's trained on Evo 2 uncover several biologically relevant features, purely from nucleotide sequences:

- Canonical gene structures (CDS, UTRs, exons).

- Structural motifs (α-helices, RNA stem-loops).

- Protein structure characteristics

How can we use these features to steer the generation of a sequence?

Steering Genomic Generation with Features

In the previous section, we saw how to steer the generation of a sequence to meet a specific heuristic function. But what if there isn’t a well-defined characteristic? What if we just want to explore the space around a generated genomic sequence to see if we can get a sequence that fits our constraints?

In general, the decision space for guiding outputs of a large model is limited to: prompt engineering, inference-time compute scaling, training models to seek specific characteristics with rewards (RL) or steering.

From Goodfire’s blog on Evo 2:

Unlike language models that process human-readable text, these neural networks operate on DNA sequences—a biological code that even human experts struggle to directly read and understand

The potential impact of steering Evo 2 is particularly significant: while language models can be prompted to achieve desired behaviors, a model that 'only speaks nucleotide' cannot. Learning to steer through features would unlock entirely new capabilities.

In Evo 2, there is no equivalent to prompt engineering because the model only understands genetic sequences. Of the other three, steering is the only category that does not require inference-time compute to scale. Rather, steering can be used to directly guide sequences towards having characteristics in the latent space of DNA without requiring an explicit heuristic function.

Especially when exploring the space around a generated sequence, steering is a powerful tool. Unfortunately, the Evo 2 team did not provide a way to steer the generation of a sequence, though the Goodfire team hints at future work in this direction.

Preliminary experiments have shown promising directions for steering these features to guide DNA sequence generation, though this work is still in its early stages.

Even without such a tool, we can still visualize the features that Evo 2 has learned to get a sense of what future support for steering might look like.

Visualizing Evo 2's Latent Space with Feature Activations

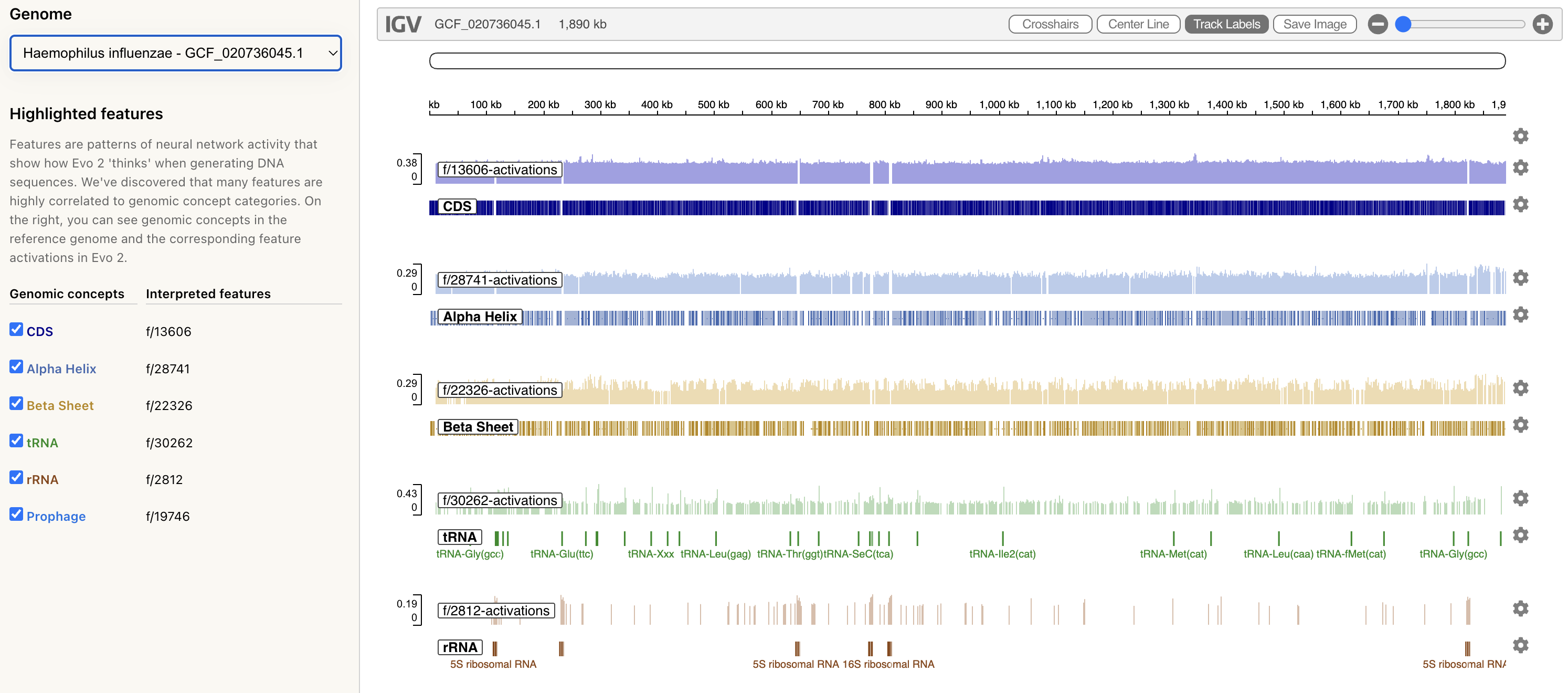

Goodfire’s mechanistic interpretability visualizer for Evo 2 annotates feature activations on genomic sequences.

In the image below, you can see the feature activations for the Haemophilus influenzae genome (the common cause of many infections). At different levels of granularity, you can see the activations for α-helices and β-sheets, as well as those at the RNA-level, such as ribosomal RNA.

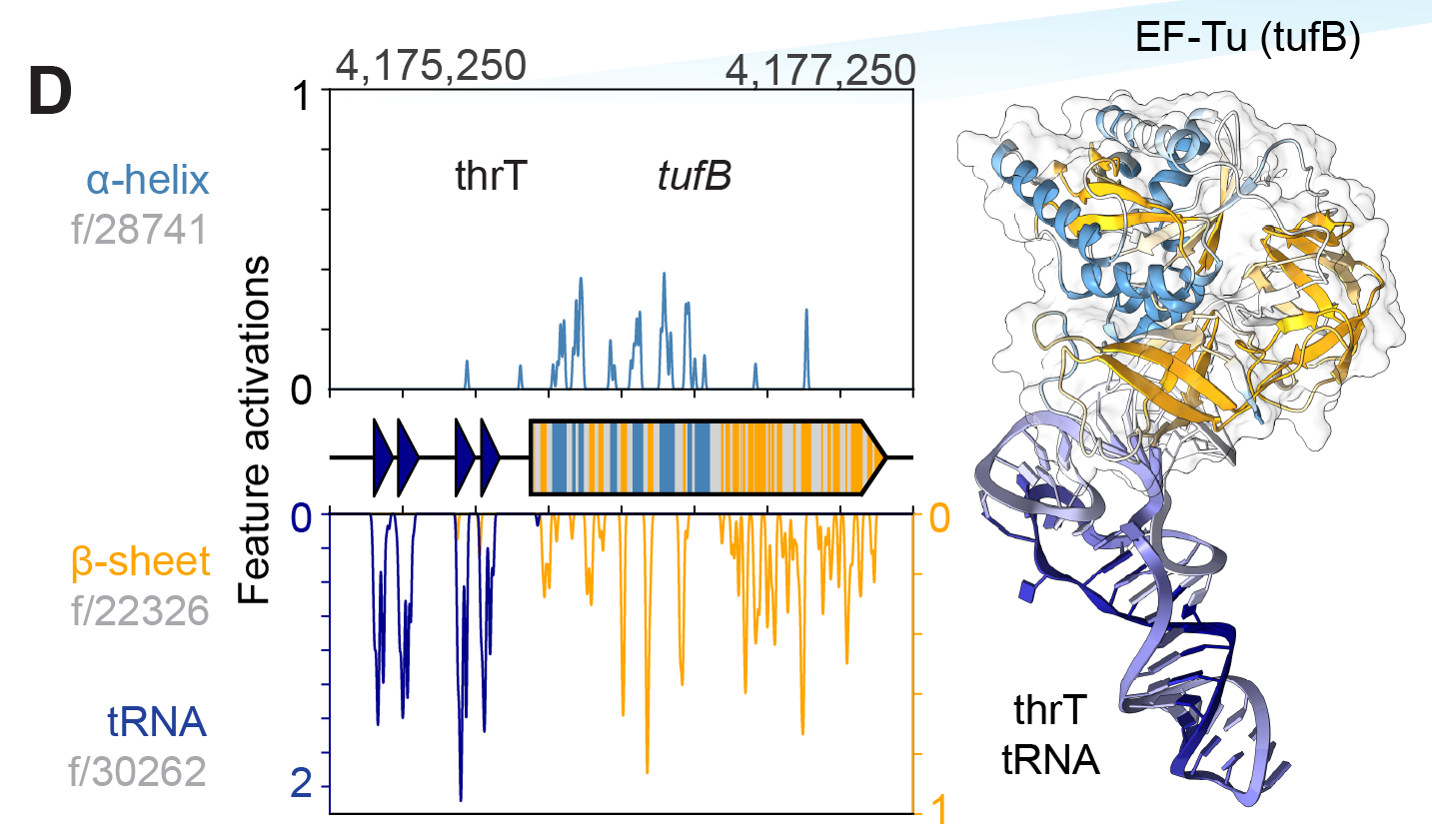

Using AlphaFold3, you can model the 3D protein structure for a nucleotide sequence. You can see in the image below that the the positional pattern of the features matches the simulated secondary-structure elements of the encoded “protein”. This is one of the cooler representations of how genomic language models “learn” the 3-D structure of proteins, without being explicitly trained on them.

Although all of the identified features above from Evo 2 are biological features which are commonplace in literature, mechanistic interpretability could discover learned representations of unknown biological features not yet documented in scientific literature. If large models can learn “deeper representations” beyond what’s known in literature, simply training a model and interpreting it could be enough to unlock new research.

Takeaways

At this point, you've learned about the architecture behind Evo 2, how it can be used to generate novel genomic sequences and how Evo 2 could identify features in the latent space of DNA. What I haven't discussed is the future of Evo 2 and where biologists will use the model.

To get a sense of the limitations and potential of Evo 2, I'd recommend reading owlposting's socratic dialogue on Evo 2. I generally agree with owlposting's high-level assessments:

- Evo 2 needs wet-lab validation for pathogenicity prediction to be used in production workflows, because it was only evaluated with digital models, not on any biological experiments.

- High-fidelity genome generation at scale is only possible with large models such as Evo 2, not through manual human design. But the utility today is bottlenecked by DNA synthesis costs.

LLMs today are useful for real-world tasks because reward models for language can already be approximated at a reasonable cost. This has been shown with RLHF for qualitative reasoning tasks and specific RL reward models for tasks such as math and coding. On the other hand, DNA foundation models like Evo 2 don’t have access to the same quantity of high fidelity data. Getting reward signals from biological systems is difficult because you need to run experiments over days or weeks, which can't be accelerated by just adding more compute. To create useful RL environments for Evo 2, you need to integrate with high-throughput biological systems. To accelerate biological research with Evo 2, we’ll need better virtual environments for training, tighter integration with high-throughput experiments, and reward modeling that bridges the computational-to-experimental gap.

Though Evo 2 is a step in the right direction towards an "App Store for Biology", a clear bottleneck in applying these models is the challenges of wet-lab biological validation. Unlike software, where closed-loop feedback and rapid iteration are possible, biological research is constrained by the cost and complexity of experiments and data collection. Progress with Evo 2 and other models will depend as much on building better experimental and data infrastructure as on advances in model design.

Thanks to Chris Zou and Darya Kaviani for their feedback & support on this post! I appreciated Asimov's post on Evo 2 and owlposting's socratic dialogues, which were both an inspiration for this post.